Wearable Smart Devices for Real-Time Position Correction

The Role of Wearable Smart Devices in Changing Neck And Back Pain Therapies

As we enter the advanced landscape of medical care in 2025, pain in the back continues to be a relentless condition impacting millions worldwide. New Research: Top 3 Breakthroughs in Back Pain Relief . However, the introduction of wearable clever devices for real-time pose adjustment stands apart as a beacon of development, guaranteeing a revolutionary technique to minimizing this old-time trouble. This essay looks into the transformative potential of such gadgets in the world of back pain therapies.

Gone are the days when pain in the back sufferers depend only on routine check outs to a physio therapist or chiropractic physician. With the introduction of wearable smart gadgets customized for position correction, individuals are now empowered to organize their back health in actual time. These cutting-edge gadgets are ingeniously designed to be light-weight, unobtrusive, and perfectly integrated into the daily lives of customers.

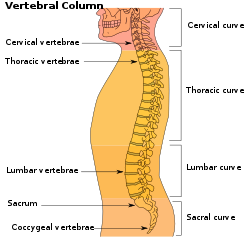

At the heart of these devices lies the innovative blend of sensing units and artificial intelligence. Sensing units continually keep an eye on the users position throughout the day, spotting slouches, imbalances, and any type of inconsistencies from a healthy and balanced back curvature. When bad position is identified, the tool sends out gentle vibrations or acoustic cues, motivating the customer to readjust their setting. This instantaneous feedback loophole not just assists in remedying posture in the moment but additionally trains the muscle mass and mind to preserve an ideal stance gradually, properly minimizing stress and anxiety on the back.

Furthermore, the real-time data accumulated by these tools provides important insights right into postural behaviors, helping customers to determine patterns and activities that add to their back pain. By syncing with mobile phones or various other clever technologies, the tool can supply individualized guidance, workouts, and also leisure strategies, all customized to the users particular demands and development.

The implications of this innovation are profound for preventative care. By resolving poor position before it becomes a chronic problem, these wearable devices have the possible to substantially reduce the occurrence of pain in the back, which subsequently could reduce the need for even more invasive treatments like surgery or long-lasting medicine.

Moreover, the integration of such tools right into telehealth services boosts the range of remote medical diagnosis and treatment. Individuals can share their stance data with doctor, enabling more exact evaluations and customized treatment plans without the need for regular in-person gos to.

To conclude, as we seek to 2025 and past, wearable smart gadgets for real-time posture improvement attract attention as an innovative treatment for neck and back pain. By merging the benefit of wearable technology with the accuracy of real-time information, these devices offer a proactive technique to spinal

Genetics Therapy for Long-Term Pain Alleviation

Gene Treatment for Long-Term Pain Alleviation: A Peek right into the Future of Neck And Back Pain Management

The year is 2025, and the landscape of back pain treatment is seeing a transformative age, identified by technology and advanced technology. Among one of the most advanced treatments that have actually arised, genetics therapy sticks out as a sign of hope for those that deal with persistent neck and back pain. This unique method is not just introducing in its approach but likewise promises long-lasting relief, which has been a distant dream for several people.

Genetics therapy for back pain operates on a principle that is as sophisticated as it is intricate-- it includes the alteration of a people genes to treat or avoid condition. In the context of neck and back pain, this treatment targets the hereditary elements that add to the swelling, nerve damage, and cells deterioration that are frequently at the origin of persistent pain.

The process of gene therapy begins with the recognition of details genetics that influence pain feeling or inflammatory reactions. Researchers have made significant strides in this area, determining hereditary markers that can be controlled to decrease pain without the requirement for repeated medicine programs. As soon as these genes are determined, a safe infection or one more vector is genetically crafted to lug healthy and balanced or tweaked genetics right into the human cells.

Clients going through genetics therapy for back pain obtain a shot straight into the affected location of the back. This localized method ensures that the restorative genetics get to the desired site, supplying a targeted treatment that lessens systemic negative effects. The presented genes then function to either reduce the overactive pain signals or advertise the recovery of broken cells.

What sets gene treatment besides conventional pain management techniques is its capacity for lasting relief. Rather than covering up signs with painkillers or going through intrusive surgical treatments, individuals can eagerly anticipate a future where their bodys own hereditary make-up is harnessed to battle pain from within. As the changed genes integrate right into the patients DNA, the therapeutic impacts can maintain for years, significantly improving the quality of life for those afflicted with chronic pain in the back.

Additionally, gene therapy is customized. Each treatment can be customized to the individuals hereditary account, enhancing the performance and reducing the chance of damaging reactions. This bespoke technique to pain monitoring declares a brand-new era of accuracy medicine, where therapies are designed to fit each clients special hereditary plan.

The promise of genetics treatment for lasting pain relief is not without its difficulties. The road to prevalent medical application has actually been led with strenuous screening, honest factors to consider, and governing authorizations. Nonetheless, the strides made

Virtual Truth as a Device for Chronic Pain In The Back Monitoring

Online Reality as a Tool for Chronic Neck And Back Pain Management: A Peek right into the Future of Healing

As we venture much deeper right into the 21st century, the world of pain management is going through a change, one that merges the borders between modern technology and human feeling. Online Truth (VR), when a fantasy of sci-fi, has now come to be a sign of hope for those experiencing chronic back pain. In the advanced landscape of 2025, VR isn't merely a device for entertainment yet an innovative restorative method that is redefining the way we come close to back pain treatment.

The principle of using virtual reality for chronic neck and back pain monitoring comes from its capability to submerse patients in an alternating reality, one where the constraints and pains of their physical bodies can be gone beyond. This immersive experience is more than just an interruption; it's a kind of cognitive behavior modification that instructs people just how to much better understand and handle their pain.

In a regular virtual reality neck and back pain administration session, individuals wear a virtual reality headset and are transferred to calm atmospheres, be it a sunlit woodland glade or a peaceful beach. These setups are not random; they are carefully crafted to advertise leisure and mindfulness. The person participates in assisted workouts and activities made to promote movement, versatility, and stamina, all within the comfort of a digital world that decreases the concern of pain that frequently accompanies physical treatment.

The scientific research behind this innovative method depends on the brains ability to be tricked by virtual stimuli. As individuals browse their online surroundings, their brains are coaxed right into producing pain-inhibiting feedbacks. This phenomenon, called "" virtual reality analgesia,"" has revealed appealing cause minimizing the understanding of pain. Additionally, VRs interactive nature encourages active involvement, which is important in the recovery process.

The psychological benefits of virtual reality treatment are just as remarkable. Persistent pain in the back can frequently result in anxiety, anxiety, and a sense of seclusion. With virtual reality, individuals connect with an area of fellow sufferers and doctor, promoting a sense of support and camaraderie that is important for psychological health. They learn dealing strategies and mindfulness techniques that not only aid handle pain however also boost their total quality of life.

As we accept these introducing treatments in 2025, we see a shift from a dependence on drugs to a much more holistic technique to pain monitoring. VR treatment is not a standalone remedy yet a corresponding treatment that improves standard therapies such as physical treatment, medication, and interventional treatments. It represents a tailored approach,

Custom-made 3D-Printed Back Implants and Sustains

In the evolving landscape of clinical modern technology, the realm of orthopedic care has been especially changed by the development of tailored 3D-printed spine implants and supports. As we look in the direction of 2025, this innovative method stands as a beacon of expect those dealing with chronic pain in the back, heralding a brand-new era of personalized and effective treatment alternatives.

Personalized 3D-printed spine implants and supports are an item of the marital relationship in between innovative imaging techniques and sophisticated 3D printing technology. By making use of detailed scans of an individuals one-of-a-kind spinal anatomy, physician can now create implants and sustains that are customized to the people details needs. This degree of customization makes certain that the implants fit perfectly, lessening the threat of being rejected and difficulties that can arise from ill-fitting, mass-produced options.

The effects for pain in the back sufferers are extensive. For many, standard back surgical treatment can be an overwhelming prospect, with long recovery times and the potential for only partial relief from pain. Nonetheless, with the accuracy used by 3D printing, specialists can target the damaged location with a much greater level of accuracy, leading to more successful results. This can lead to significantly reduced pain, boosted movement, and a quicker go back to daily activities.

In addition, the products utilized in 3D printing can be chosen for their compatibility with the human body and their toughness. This means that the implants can be developed not just to offer architectural support yet additionally to assist in the bodys natural healing procedures. Some 3D-printed products can also promote bone growth, leading to a more powerful, more incorporated repair work with time.

For those with degenerative problems or complicated spine issues, personalized 3D-printed implants stand for a quantum leap onward. Patients who may have encountered a life time of pain and minimal movement currently have the possible to enjoy an extra active and comfy life. The degree of personalization in the implants can address the root cause of pain with unmatched accuracy, reducing the demand for pain medicines and additional interventions.

In 2025, as this innovation ends up being extra widespread and easily accessible, we can expect a considerable shift in exactly how back pain is treated. Customized 3D-printed spine implants and supports will likely end up being the criterion of care, supplying hope and healing to the numerous people afflicted by pain in the back. This is really a cutting edge advancement; one that assures to redefine the boundaries of spine treatment and recover the lifestyle to countless people around the world.